When researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication conducted a survey to see if “informed consent” practices are working online with regard to user data gathering, the results revealed weaknesses in a framework that, for decades, has served as the basis for online privacy regulation in the US. This framework, which is commonly known as “notice of consent,” usually allows organizations to freely collect, use, keep, share, and sell customer data provided they inform them about their data-gathering practices and get their consent. However, as the New York Times noted, the survey results add another voice to “a growing body of research suggesting that the notice-of-consent approach has become obsolete.”

“Informed consent is a myth”

The report, entitled “Americans Can’t Consent to Companies’ Use of Their Data,” contains the results, expert analyses, and interpretation of survey results. The authors not only give attention to the gap in American users’ knowledge of how companies use their data but also reveal their deep concern about the consequences of its use yet feel powerlessness in protecting it. Believing they have no control over their data and that trying would be pointless is what the authors call “resignation,” a concept they introduced in 2015 in the paper, “The Tradeoff Fallacy.”

As the Annenberg School report said:

“High percentages of Americans don’t know, admit they don’t know, and believe they can’t do anything about basic practices and policies around companies’ use of people’s data.”

The authors define genuine consent as people having “knowledge about commercial data-extraction practices as well as a belief they can do something about them.” The survey finds that Americans have neither.

“We find that informed consent at scale is a myth, and we urge policymakers to act with that in mind,” the report said.

The New York Times noted a handful of regulators agreeing to the report’s findings.

“When faced with technologies that are increasingly critical for navigating modern life, users often lack a real set of alternatives and cannot reasonably forgo using these tools,” said Lina M. Khan, a chairperson of the Federal Trade Commission, in a speech last year.

Digital consent has had critics as early as 1999, denoting that its weakness remained unaddressed for almost 25 years. Paul Schwartz, a professor at the University of California and author of the paper “Privacy and Democracy in Cyberspace,” had warned that consent that was given via privacy policy notices was “unlikely to be either informed or voluntarily given.” The notices were “meaningless,” he said, as most people ignore them, were written in a vague and legalistic language that very few people understand, and “fail to present meaningful opportunities for individual choice.”

Neil Richards and Woodrow Hartzog, authors of the paper “The Pathologies of Digital Consent,” give strength to this argument by recognizing a form of consent they call “unwitting consent,” which occurs when people do not really understand “the legal agreement,” “the technology being agreed to,” and “the practical consequences or risks of agreement.” Previous work of two of the authors of the study also shows people misunderstanding and confusing the meaning behind the term “privacy policy,” believing it is a promise that the company asking for consent will protect the privacy of the one giving consent.

Robert Levine’s argument is also in parallel with Richards and Hartzog. He expressed that people must have understanding and autonomy before they can make informed choices. That said, a person must understand corporate practices and policies (including legal protection), surrounding the data that companies want to gather about users. A person must also believe that companies will give them the freedom to decide whether to give up their data and when, Levine said. If one of these isn’t satisfied, the consent to data collection “is involuntary, not free, and illegitimate.”

‘F’ for Fail

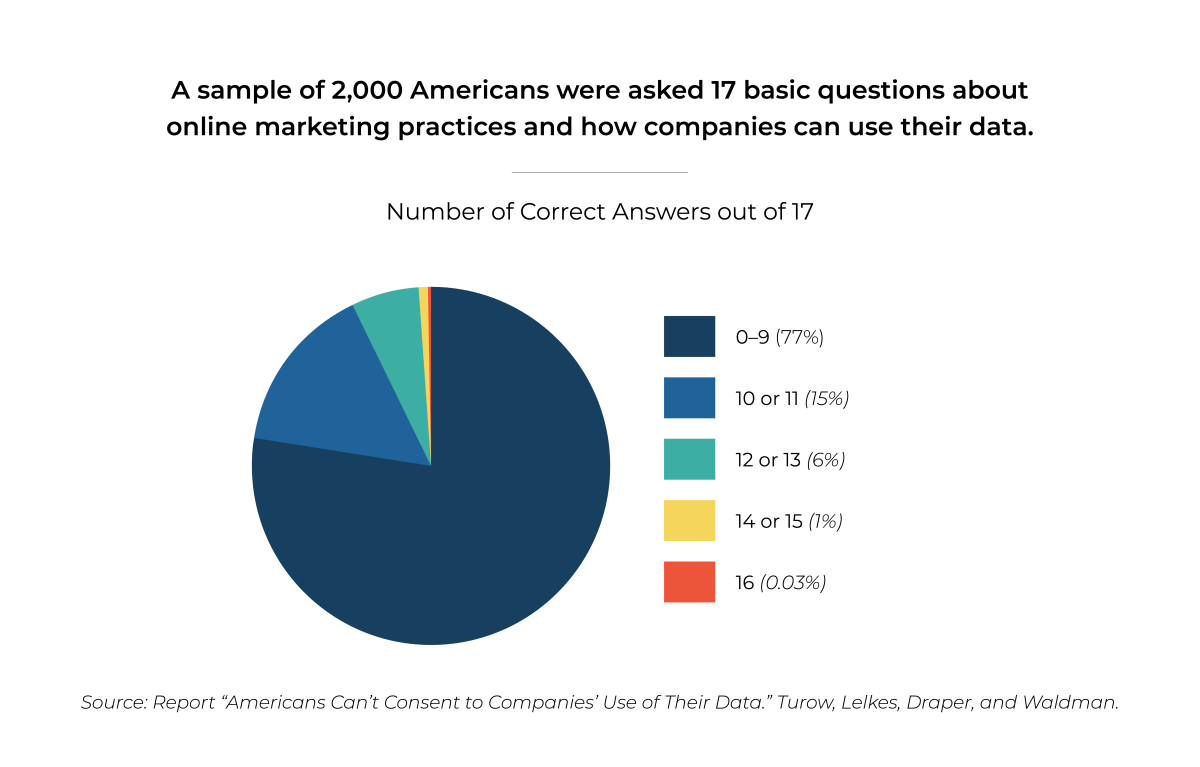

The study presupposes that in order to give consent, US consumers must satisfy two things: they must be informed about what is going to happen to their data, and they must have the ability to give (or withdraw) consent. To test these, 2,000 US survey participants are provided a set of 17 basic true/false questions about internet practices and policies. They can also answer “I don’t know,” the median option.

The overall survey results are worrying.

A majority (77 percent) of survey takers got nine or fewer correct answers out of 17 questions, which could be interpreted as an ‘F’ grade. Only one participant got an ‘A’ grade, scoring 16 correct answers. Below are the most notable insights from the results:

* Only around 1 in 3 Americans know it is legal for an online store to charge people different prices depending on where they are located.

* More than 8 in 10 Americans believe, incorrectly, that the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) stops apps from selling data collected about app users’ health to marketers.

* Fewer than one in three Americans know that price-comparison travel sites such as Expedia or Orbitz are not obligated to display the lowest airline prices.

* Fewer than half of Americans know that Facebook’s user privacy settings allow users to limit some of the information about them shared with advertisers.

Furthermore, 80 percent of Americans believe Congress must act urgently to regulate how companies use personal information. Joseph Turow, one of the authors of the study, worries though that the longer the government waits to enforce change, the more difficult it will be to control user data.

“For about 30 years, big companies have been allowed to shape a whole environment for us, essentially without our permission,” Turow said. “And 30 years from now, it might be too late to say, ‘This is totally unacceptable.'”

We don’t just report on threats—we remove them

Cybersecurity risks should never spread beyond a headline. Keep threats off your devices by downloading Malwarebytes today.