Ransomware peddlers have come up with yet another devious twist on the recent trend for data exfiltration. After interviewing several victims of the Clop ransomware, ZDNet discovered that its operators appear to be systematically targeting the workstations of executives. After all, the top managers are more likely to have sensitive information on their machines.

If this tactic works, and it might, it’s likely that other ransomware families will follow suit, just as they’ve copied other successful tactics in the past.

What is Clop ransomware?

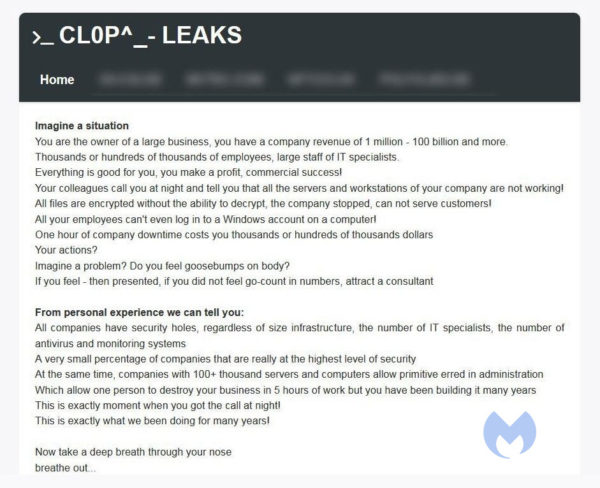

Clop was first seen in February 2019 as a new variant in the Cryptomix family, but it has followed its own path of development since then. In October 2020 it became the first ransomware to demand a ransom of over $20 million dollars. The victim, German tech firm Software AG, refused to pay. In response, Clop’s operators published confidential information they had gathered during the attack, on a dark web website.

Copycat tactics

When we first came across file-encrypting ransomware, we were astounded and horrified at the same time. The simplicity of the idea—even though it took quite a bit of skill to perfect a sturdy encryption routine—was of a kind that you immediately recognize as one that will last.

Since then, ransomware has developed in ways we have seen before in other types of malware, but it has also introduced some completely new techniques. Clop’s targeting of executives is just the latest in list of innovations we’ve witnessed over the last couple of years.

Let us have a quick look at some of these innovations ranging from technical tricks to advanced social engineering.

Targeted attacks

Most of the successful ransomware families have moved away from spray-and-pray tactics to more targeted attacks. Rather than trying to encrypt lots of individual computers using malicious email campaigns, attackers break into corporate networks manually, and attempt to cripple entire organisations.

An attacker typically accesses a victim’s network using known vulnerabilities or by attempting to brute-force a password on an open RDP port. Once they have gained entry they will likely try to escalate their privileges, map the network, delete backups, and spread their ransomware to as many machines as they can.

Data exfiltration

One of the more recent additions to the ransomware arsenal is data exfiltration. During the process of infiltrating a victim’s network and encrypting its computers, some ransomware gangs also exfiltrate data from the machines they infect. They then threaten to publish the data on a website, or auction it off. This gives the criminals extra leverage against victims who won’t, or don’t need to, pay to decrypt their data.

This extra twist was introduced by Ransom.Maze but is also used by Egregor, and Ransom.Clop as well, as we mentioned above.

Hiding inside Virtual Machines

I warned you about technical innovations. This one stands out among them. As mentioned in our State of Malware 2021 Report, the RagnarLocker ransomware gang found a new way to encrypt files on an endpoint while evading anti-ransomware protection.

The ransomware’s operators download a virtual machine (VM) image, load it silently, and then launch the ransomware inside it, where endpoint protection software can’t see it. The ransomware accesses files on the host system through the guest machine’s “shared folders.”

Encrypting Virtual Hard Disks

Also mentioned in the State of Malware 2021 Report was the RegretLocker ransomware that found a way around encrypting virtual hard disks (VHD). These files are huge archives that hold the hard disk of a virtual machine. If an attacker wanted to encrypt the VHD, they would endure a painfully slow process (and every second counts when you’re trying not to get caught) because of how large these files are.

RegretLocker uses a trick to “mount” the virtual hard disks, so that they are as easily accessible as a physical hard disk. Once this is done, the ransomware can access files inside the VHD and encrypt them individually, steal them, or delete them. This is a faster method of encryption than trying to target the entire VHD file.

Thwarting security and detection

Ransomware is also getting better at avoiding detection and disabling existing security software. For example, the Clop ransomware stops 663 Windows processes (which is an amazing amount) and tries to disable or uninstall several security programs, before it starts its encryption routine.

Stopping these processes frees some files that it could not otherwise encrypt, because they would be locked. It also reduces the likelihood of triggering an alert, and it can hinder the production of new backups.

What next?

It remains to be seen if Clop’s new tactic will be copied by other ransomware families or how it might evolve.

It has been speculated that the tactic of threatening to leak exfiltrated data has lowered some victims’ expectations that paying the ransom will be the end of their trouble. Targeting executives’ data specifically may be a way to redress this, by increasing the pressure on victims.

Clop, or a copycat, may also try to use the information found on managers’ machines to spread to other organisations. Consider, for example, the method known as email conversation thread hijacking, which uses existing email conversations (and thus trust relationships) to spread to new victims. Or the information could be sold to threat actors that specialize in business email compromise (BEC).

For those interested, IOCs and other technical details about Clop can be found in the Ransom.Clop detection profile.