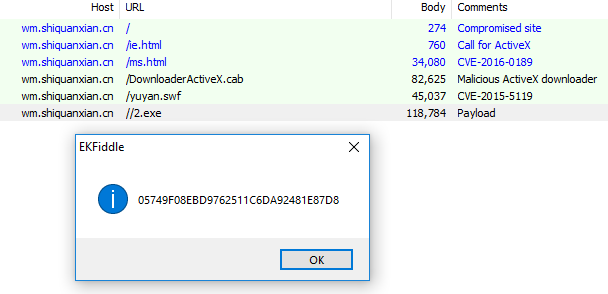

Recently, we described an unusual Chinese drive-by attack that was delivering a variant of the Avzhan DDoS bot. The attack also contained multiple components that were not-so-new. Among the exploits, the newest was from 2016. Avzhan is also not a recent malware—the compilation timestamp of the unpacked payload was from August 2015. But there was one more unusual thing that triggered our attention. The outer layer of Avzhan matched the signatures of Virut, a malware that’s been dead in the water since 2013.

At first, it was hard to believe this detection. Who would want to distribute such an old piece of malware that is no longer developed, and whose CnC servers were sinkholed long ago by Polish CERT? Maybe it was the author of the packer by which the DDoS bot was wrapped incorporating some Virut-like obfuscation?

After further research, it turned out the detection was not wrong. The Avzhan bot carried along with it a legitimate Virut. But it is unlikely that the distributors added it intentionally. Rather, the server from where the attack was deployed happened to be infected with Virut. The virus attached as a parasite to the distributed DDoS malware, and was dropped with the drive-by attack into new places. Interestingly, in 2016 Virut’s code was also found in Chinese cameras. Similarly, the computers of developers were infected with Virut, and by this way its code got passed further.

Since Virut has made this unexpected reappearance, we will have a look at how it works in this post.

Analyzed sample

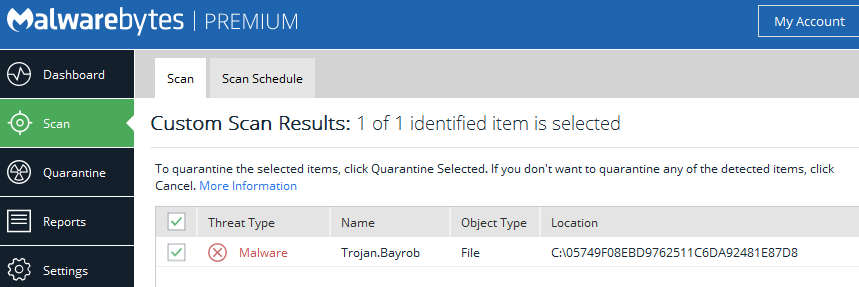

05749f08ebd9762511c6da92481e87d8 – the main sample, dropped by the exploit

Behavioral analysis

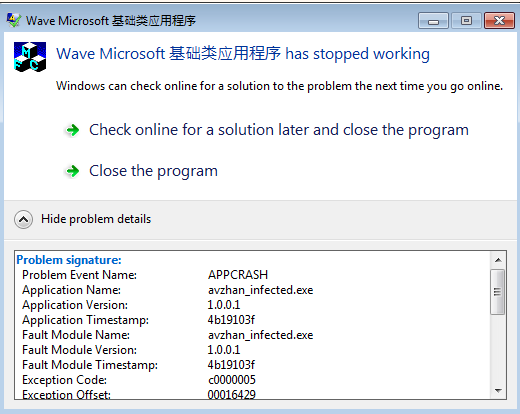

Virut behaves like a typical, old-fashioned infectious virus. As we observed, samples infected by Virut always crashed on 64-bit systems.

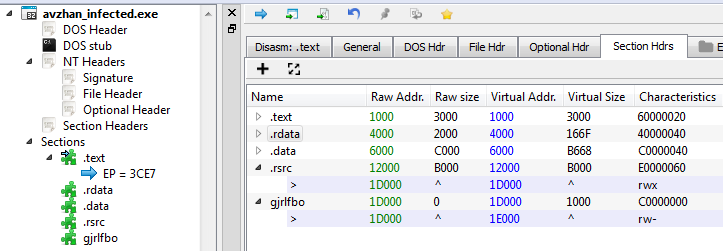

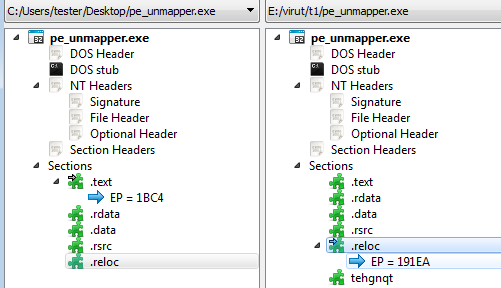

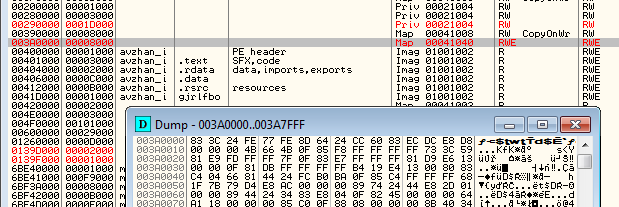

However, when deployed in a 32-bit environment, Virut spread like fire, trying to infect all executables it could reach by attaching its own code. The code of Virut is polymorphic and designed with great care, so the infection patterns are not easy to grasp. Often (if there is enough space), Virut adds a new, empty section with a random name, for example:

If there is no space for a new header in the input file, this step is omitted. So, the absence of the added section does not guarantee that the file is clean. Another suspicious indicator may be that the last section is set to RWX (Read-Write-eXecute).

Virut changes sizes of the sections and the entry point of the application in order to redirect to its own code. After the malicious code is deployed, the original entry point is executed. So, from the user’s point of view, the infected application works as before.

In addition to infecting files on the disk, Virut attacks running processes as well. So, even if the first infected process was killed, the malicious code keeps running in the memory.

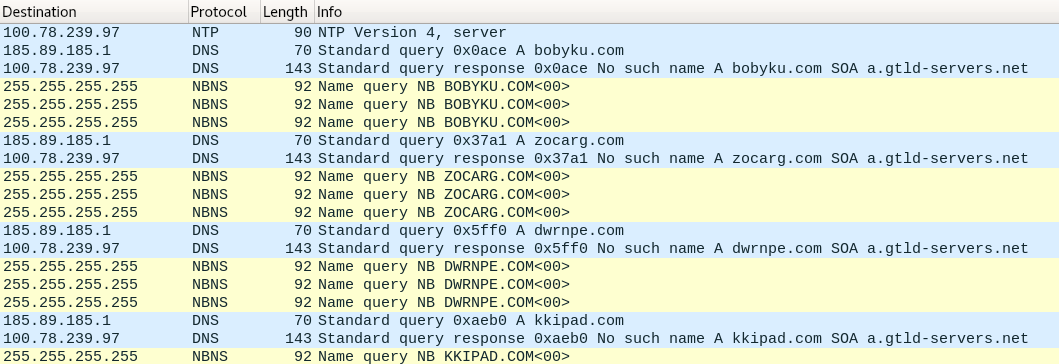

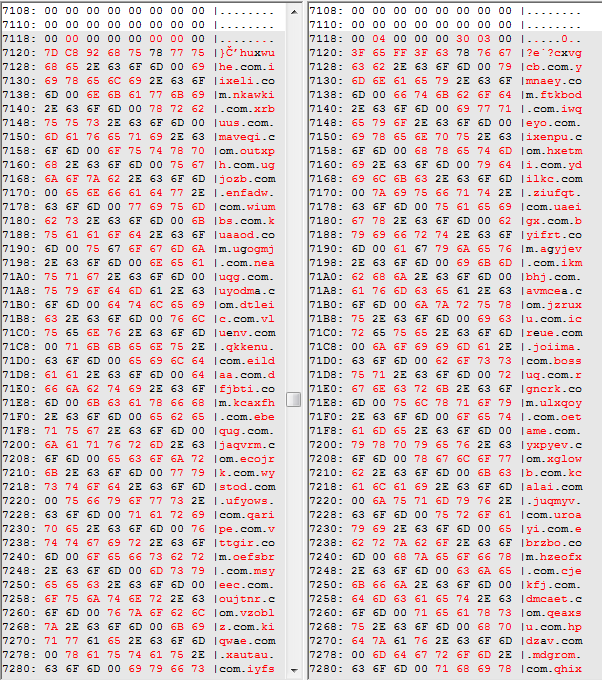

The malware uses some hardcoded CnC addresses, as well as a DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm). Looking at the network traffic, we can see the queries to the domains follow the pattern of using six letters before the dot com: 6{a-z}.com

Due to the fact that the full infrastructure of Virut was sinkholed, none of its CnC servers are active.

Inside

Infection patterns

As mentioned before, Virut’s code can mutate—each infection looks different. Some of the chosen patterns depend on the features of the input.

In PE files, each section must be aligned to the minimal unit that is indicated by a file alignment field in the PE header. This is why sometimes there is an empty space between one PE section and the other, filled only with padding. This empty space is called the cave. Old infectors often used this space to implant their own code. This is what Virut also tries to do.

In the example below, a cave after the .text section has been filled with malicious code:

Depending on the input, there may not be sufficient caves between sections. Then, Virut adds its code just at the end of the last section:

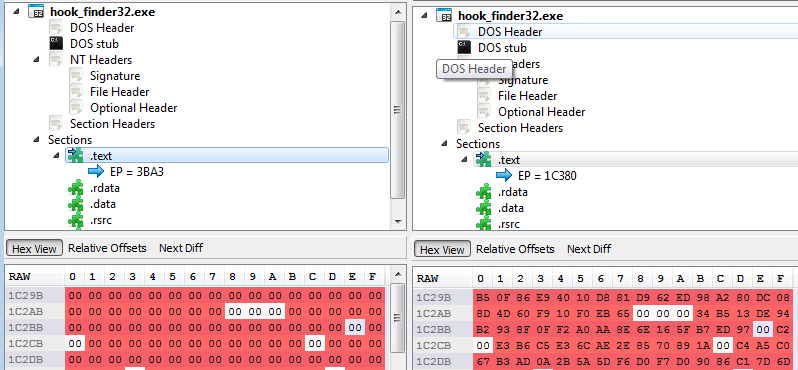

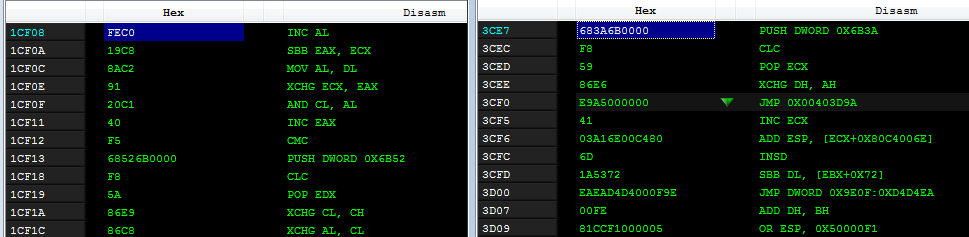

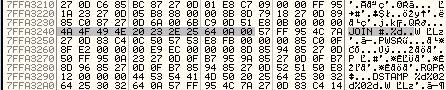

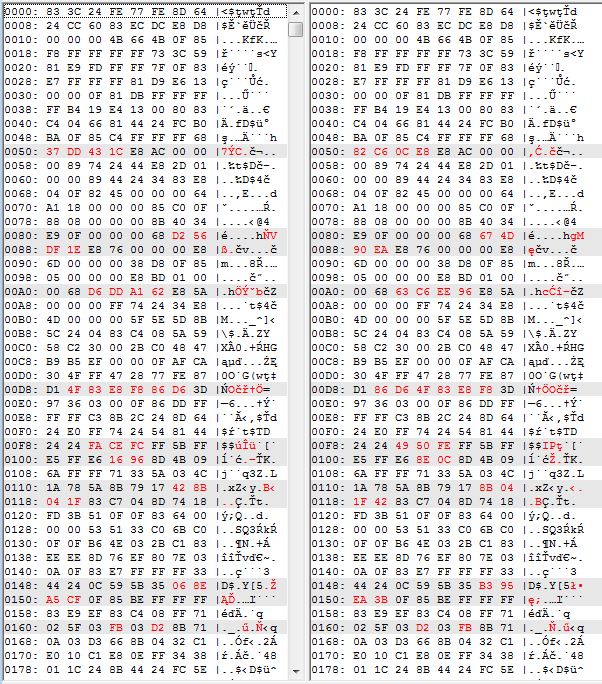

But this is not the only thing that impacts the features of the infection. The code generated by Virut is polymorphic, so the same file will not be infected twice in the same way. Below is a comparison of code from the same application, infected by Virut in two different runs:

Virut’s shellcode

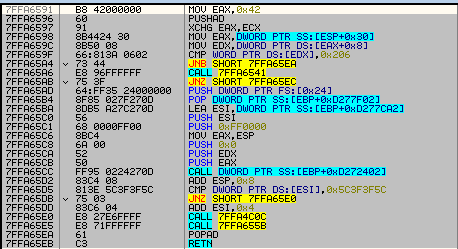

The code appended to the infected files makes an initial stub that unpacks in the memory of Virut’s shellcode. That is a heart of the malware. This is how the unpacked shellcode looks:

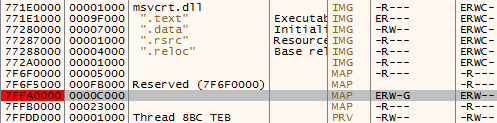

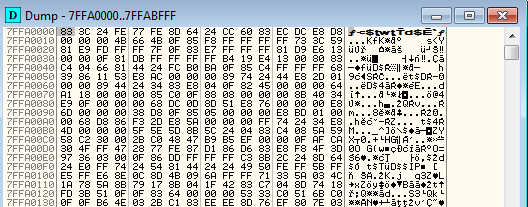

The same code is also injected into other processes. It is implanted in a new page in the memory. Example:

The shellcode contains the functionality of a userland rootkit. It hooks NTDLL within every infected process so that each time the specific function is called, the execution is redirected first to Virut’s implant. There are seven functions that are hooked:

- NtCreateFile

- NtCreateProcess

- NtCreateProcessEx

- NtCreateUserProcess

- NtDeviceIoControlFile

- NtOpenFile

- NtQueryInformationProcess

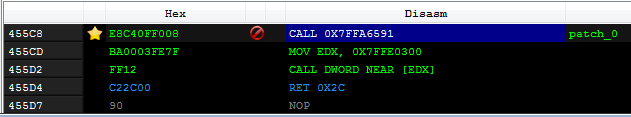

Below you can see an example of the hooked function

NtCreateFile. As you can see, the first instruction is a call to the malicious memory page:

And this is how the code looks that is being called:

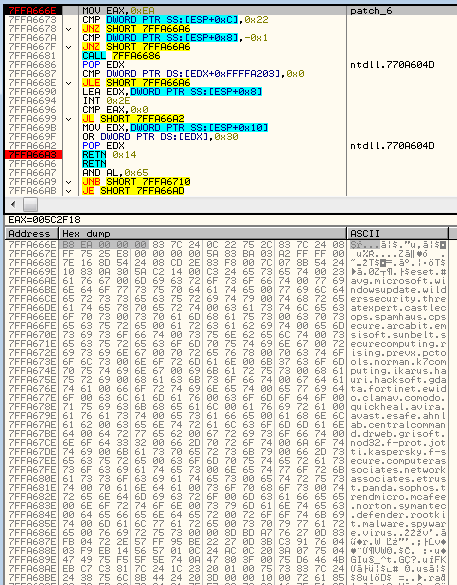

We also find the lists of AV products, that Virut uses in order to check if it is running in the controlled environment:

Apart from the rootkit, it contains the code responsible for communication with the CnC. For example, among the embedded strings we found IRC commands that suggest that IRC was part of Virut’s communication:

List of command patterns:

PING NICK nrmbhoz PRIV JOIN #.%d DSTAMP %s%02d%02d

There are also hardcoded addresses of the CnCs. Two servers are static and always occur in Virut samples (both of them are sinkholed by Polish CERT):

ilo.brenz.pl ant.trenz.pl

But, we can also see the domains generated by the Virut’s DGA:

While the code infecting the file mutates, the injected shellcode has a pretty consistent structure. If we compare dumps from two different processes, we find that most of the code is the same.

Conclusion

Nowadays, such old viruses are mostly forgotten, but it doesn’t mean that we are fully safe from them. Fortunately, most AV products can detect viruses like Virut by their signatures – but the people who decided not to use AV may still become their victims.Even their command-and-controll infrastructure is dead, the old infectors can roam around. There are old servers in the world that are left infected with old viruses, such as Virut or MyDoom. On our honeypots, we regularly get spam that is being sent from such abandoned bots.

Yet, it is unusual to encounter an old virus in wild sent by a modern-style drive-by attack. We never know how an old threat can get blended with a new one. This time we were lucky and the attack was simple, with a small reach.

Malwarebytes detects this DDoS bot binary as Trojan.Bayrob.