A couple weeks ago, two new Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) offerings for the Mac became available. These two offerings – a backdoor named MacSpy and a ransomware app named MacRansom – were discovered by Catalin Cimpanu of Bleeping Computer on May 25.

Cimpanu evidently had some trouble getting hold of samples, but on Friday analysis of MacRansom was posted by Fortinet and analysis of MacSpy was posted by AlienVault.

Both of these malware programs were advertised through Tor websites, claiming them to be “The most sophisticated Mac spyware/ransomware ever, for free.” Neither programs were directly available, but could only be obtained by emailing the authors at protonmail[dot]com email addresses.

Behavior

Despite the claims of sophistication, these malware programs are not particularly advanced. The programs provided to both Fortinet and AlienSpy were simple command-line executable files that, when run, copy themselves into the user’s Library folder.

MacSpy:

~/Library/.DS_Stores/updated

MacRansom:

~/Library/.FS_Store

Because the .DS_Stores folder and the .FS_Store file both have names starting with a period, they are hidden from view unless the user has done something to show invisible files.

As part of the installation, these programs also create LaunchAgent files for persistence – a not at all original method.

MacSpy:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.webkit.plist

MacRansom:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist

Some recent malware has had the capability to customize the install locations and names, but there’s no indication in the reports from Fortinet and AlienVault that such a feature is available in MacSpy or MacRansom, making these quite easy to detect.

MacRansom is created with a custom “trigger date,” after which time the malware detonates and encrypts the files in the user’s home folder, as well as on any connected volumes, such as external hard drives. As happened with KeRanger, which had a 3-day delay before encrypting, this delay will likely mean that few people who are using security software will actually be affected, as the malware will probably be detected before it encrypts anything.

Further, the encryption uses a symmetric key – meaning that the same key is used both to encrypt and to decrypt – that is only 8 bytes in length, making it rather weak and relatively easy to decrypt. However, the key creation process involves a random number and the resulting key is apparently not saved to the hard drive or communicated back to the authors in any way, making it impossible to decrypt the files except via brute force.

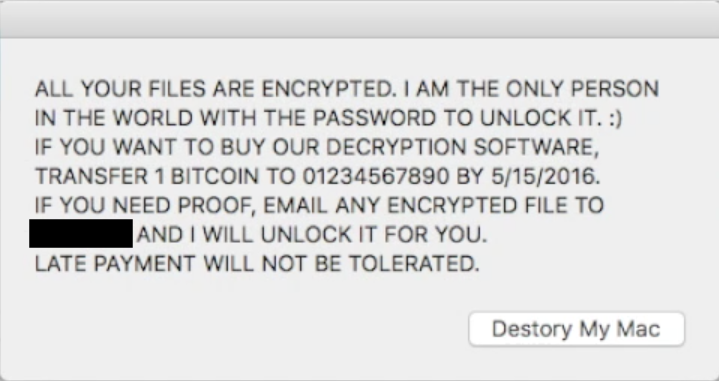

After encryption, the malware will display a pop-up alert informing the user of what must be done to decrypt the files, and will continue to reappear even if the user clicks the “Destroy [sic] My Mac” button. The malware does not save any copies of that information to files on the hard drive, as is typical of most ransomware.

MacSpy is fairly simple spyware, which gathers data into temporary files and sends those files periodically back to a Tor command & control (C&C) server via unencrypted http. It will exfiltrate the following data:

- Screenshots (taken every 30 seconds)

- Audio captured via microphone

- Keystrokes*

- Clipboard contents

- iCloud photos

- Browser data

In the case of keylogging, the malware requires an admin password, which can be provided in the email requesting a copy of the malware. This requires that the attacker knows the password for the target Mac in advance.

If the attacker pays for the malware, they will get additional capabilities, such as more general file exfiltration, access to social media, help with packaging the executable into a Trojan form (such as a fake image file), and code signing.

Analysis avoidance

Although neither of these programs is particularly sophisticated, they both do include some reasonably effective analysis avoidance features. Both include three methods for determining whether they are being analyzed by a researcher, in which case they shut down and do not display their malicious behaviors.

First, they will check to see if they are being run by a debugger, using a call to ptrace.

They will also parse the output from the shell command sysctl hw.model for the word “Mac”, terminating if that is not found. In a virtual machine, this command will not return the model identifier for the hardware, but will instead return a value specific to the virtualization software being used. Thus, if the output does not contain “Mac,” it is most likely being run in a virtual machine, and the most likely reason for that is that it’s being analyzed by a security researcher.

Another virtual machine check that is performed is a check for the number of logical and physical CPUs. Since the number of CPUs is simulated in a virtual machine, this is another fairly reliable indicator that the malware is under analysis.

If any of these checks fail, the malware terminates.

Fortunately, because the malware isn’t signed, it’s possible to hack the executables to bypass these anti-analysis checks and then analyze it in a virtual machine.

About the authors

The websites for the malware include an “About Us” section, in which the authors provide some information about their motivations:

We are engineers at Yahoo and Facebook. During our years as security researchers we found that there lacks sophisticated malware for Mac users. As Apple products gain popularity in recent years, according to our survey data, more people are switching to MacOS than ever before. We believed people were in need of such programs on MacOS, so we made these tools available for free. Unlike most hackers on the darknet, we are professional developers with extensive experience in software development and vast interest in surveillance. You can depend on our software as billions of users world-wide rely on our clearnet products.

I suspect that a lot of this is probably not accurate. I seriously doubt that they would really give away information about their former employers, which would provide a clue that could be used to help track them down and could be used as evidence in a trial. Further, as a security professional myself, it’s rather laughable that the best a security researcher could do for persistence is a launch agent.

Also, the lack of any way to decrypt files in a ransomware app is extremely amateurish. This means that 2/3 of the Mac ransomware that has ever existed has had no means for decrypting files so that users who pay will get none of their data back in return. Hopefully, this will make victims of future Mac ransomware reluctant to pay, which will, in turn, make it unprofitable to develop such malware in the future.

All these factors mean that these hackers undoubtedly do not have the qualifications they claim to have and are actually amateur developers with a tendency towards crime.

Disinfection

The presence of any of the following items is an indicator of infection:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.webkit.plist ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist ~/Library/.DS_Stores/ ~/Library/.FS_Store

Malwarebytes for Mac will detect these as OSX.MacSpy and OSX.MacRansom.

If you were infected with MacSpy, after removing it, you should be sure to change all your passwords, as they might have been compromised by the keylogging, screen captures and/or clipboard exfiltration. If your work computer has been compromised, contact your IT department to alert them to the issue; otherwise, your accounts or other information leaked could potentially give a criminal inside access to your company’s servers.

If you had a MacRansom infection and didn’t get your data encrypted, consider yourself very lucky. Start backing up your computer regularly if you didn’t already and avoid leaving the backup drive connected all the time.

If you did have data encrypted by the ransomware, it’s possible that it could be decrypted by an expert in cryptography. Although we don’t currently have information about decrypting such files, we will update this article in the future if a method for doing so is identified.